Colossi of Memnon

The Colossi of Memnon (also known as el-Colossat or el-Salamat) are two monumental statues representing Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. They are located west of the modern city of Luxor and face east looking toward the Nile River. The statues depict the seated king on a throne ornamented with imagery of his mother, his wife, the god Hapy, and other symbolic engravings. The figures rise 60 ft (18 meters) high and weigh 720 tons each; both carved from single blocks of sandstone.

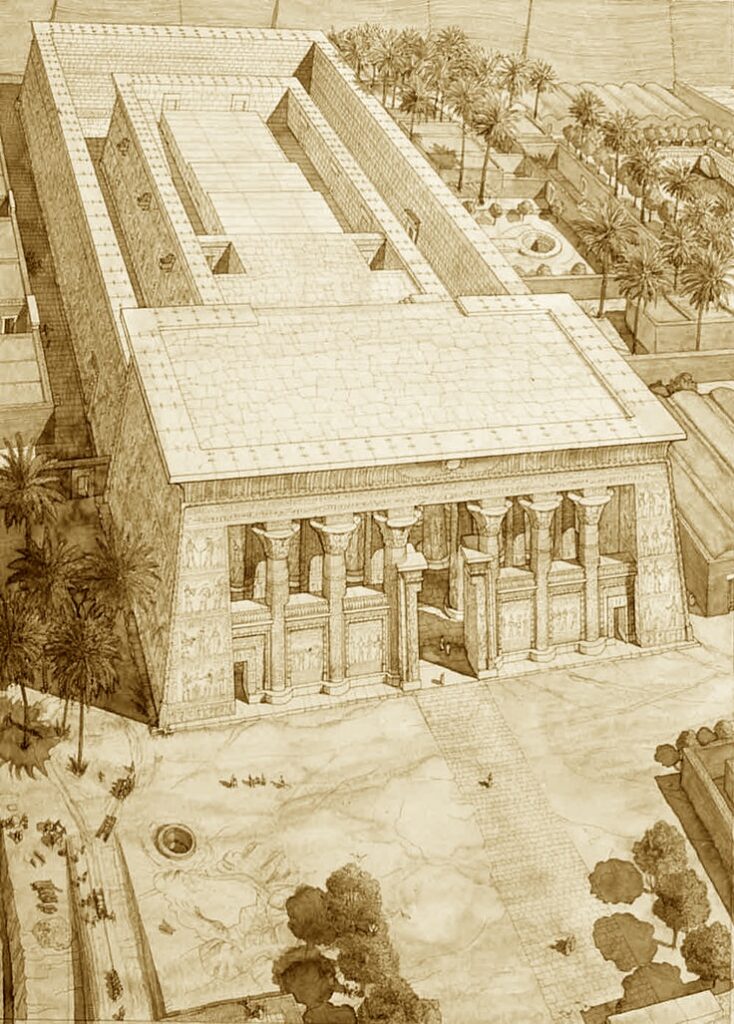

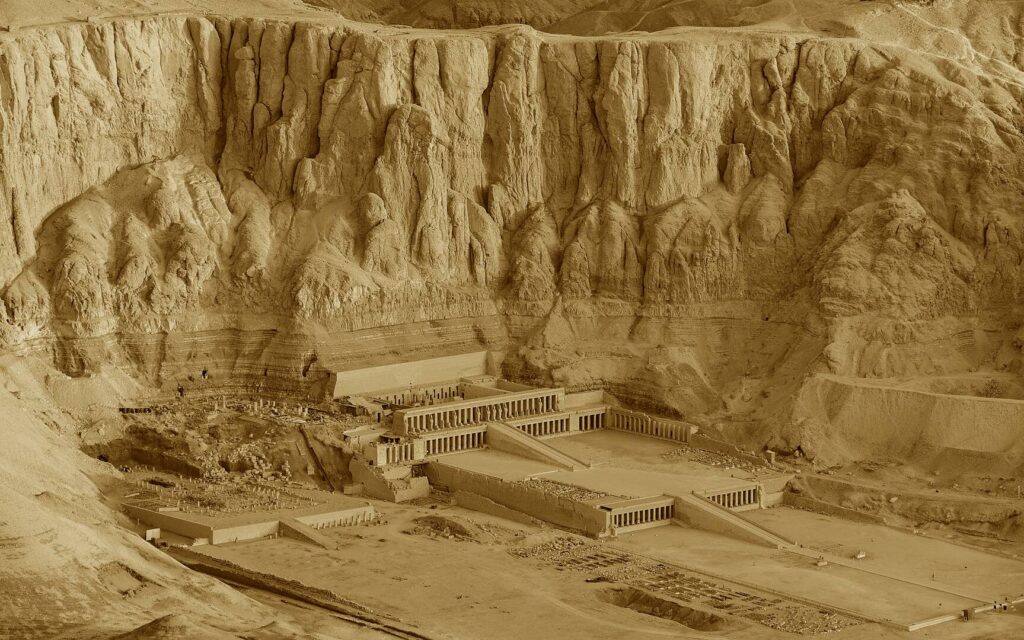

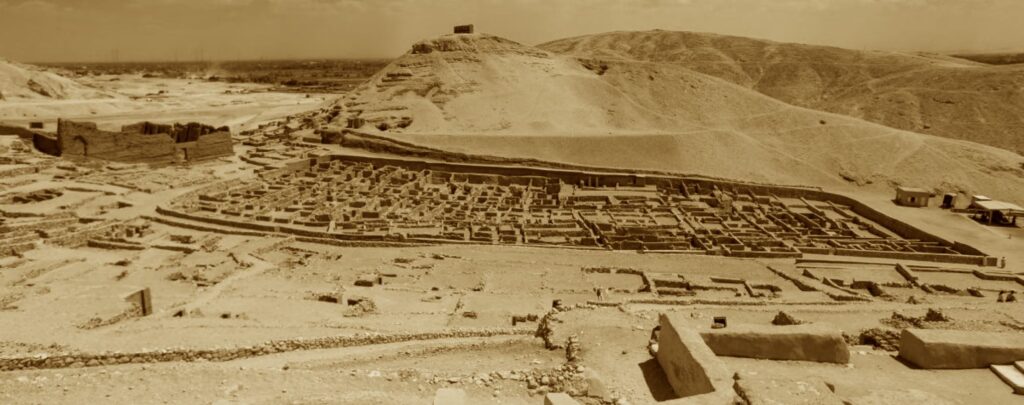

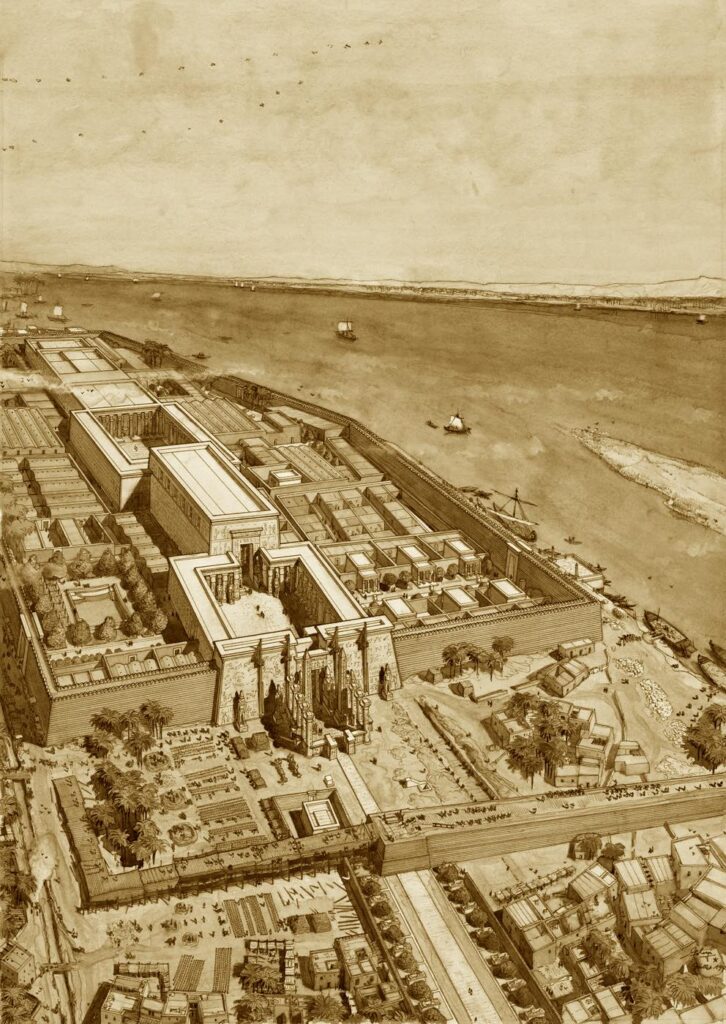

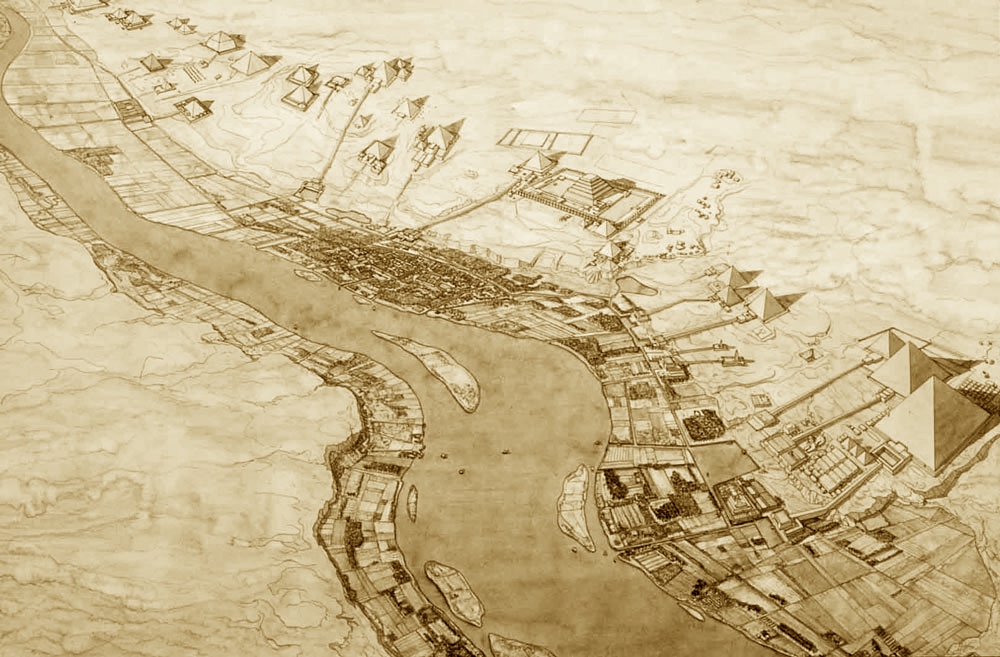

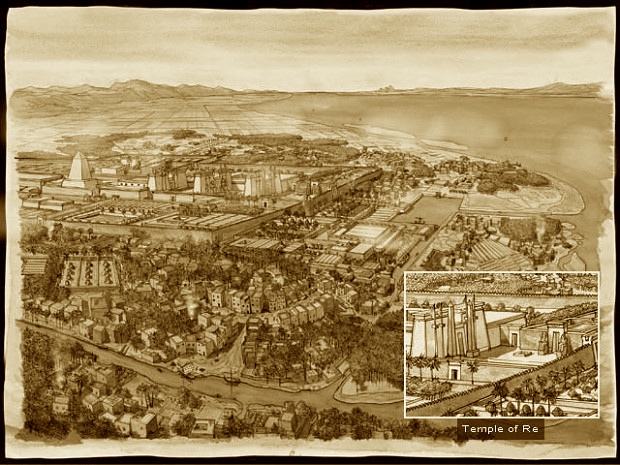

They were constructed as guardians for Amenhotep III’s mortuary complex which once stood behind them. Earthquakes, floods, and the ancient practice of using older monuments and buildings as resource material for new structures all contributed to the disappearance of the enormous complex. Little of it remains today except for the two colossal statues which once stood at its gates.

Their name comes from the Greek hero Memnon who fell at Troy. Memnon was an Ethiopian king who joined the battle on the side of the Trojans against the Greeks and was killed by the Greek champion Achilles. Memnon’s courage and skill in battle, however, elevated him to the status of a hero among the Greeks. Greek tourists, seeing the impressive statues, associated them with the legend of Memnon instead of Amenhotep III and this link was also suggested by the 3rd century BCE Egyptian historian Manetho who claimed Memnon and Amenhotep III were the same person.