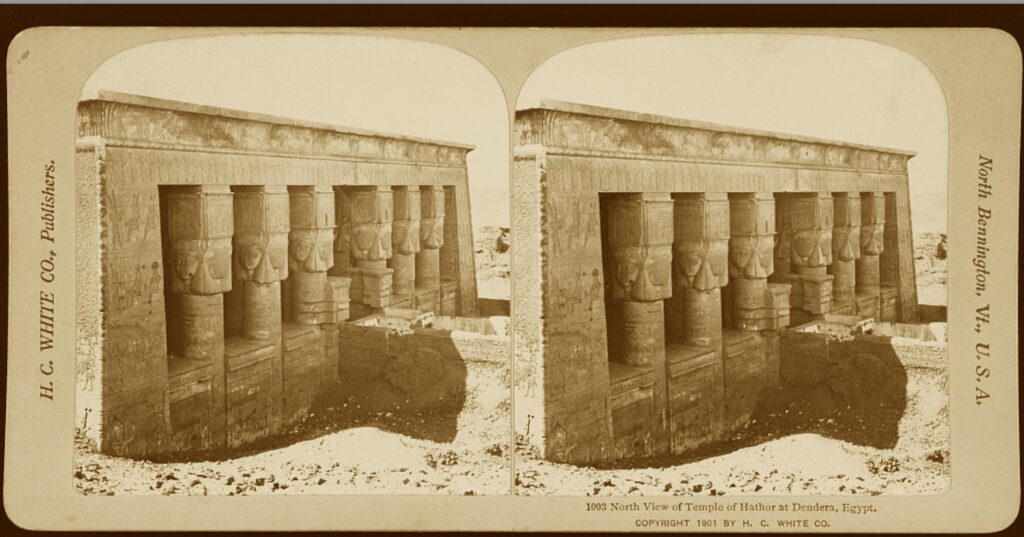

Hathor temple of Dendera

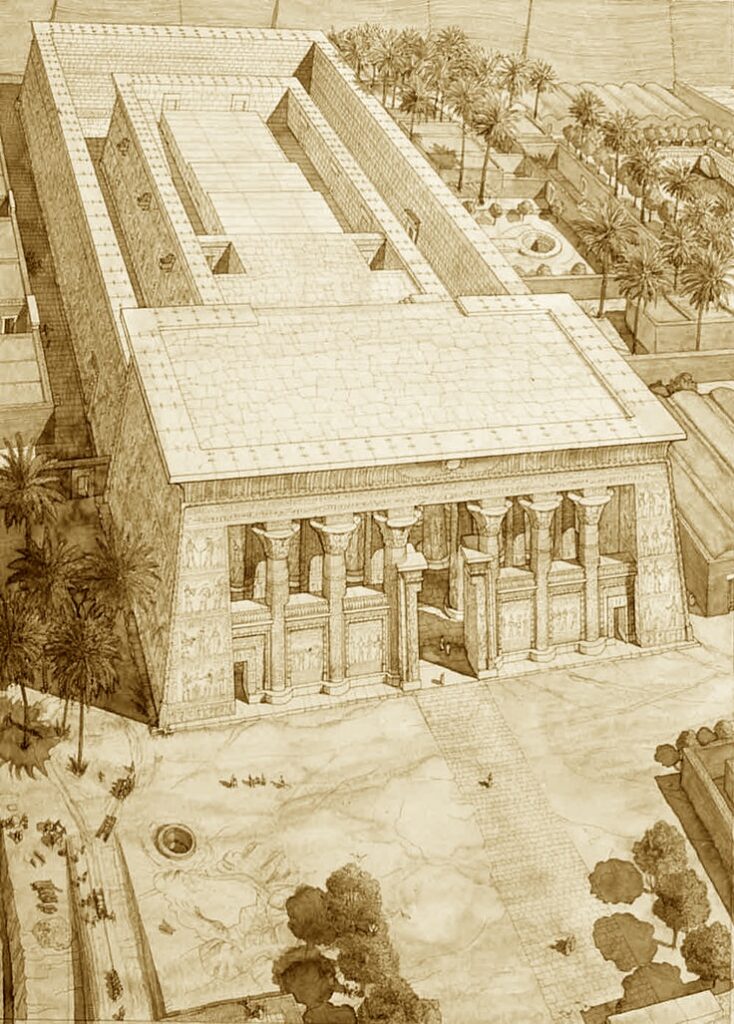

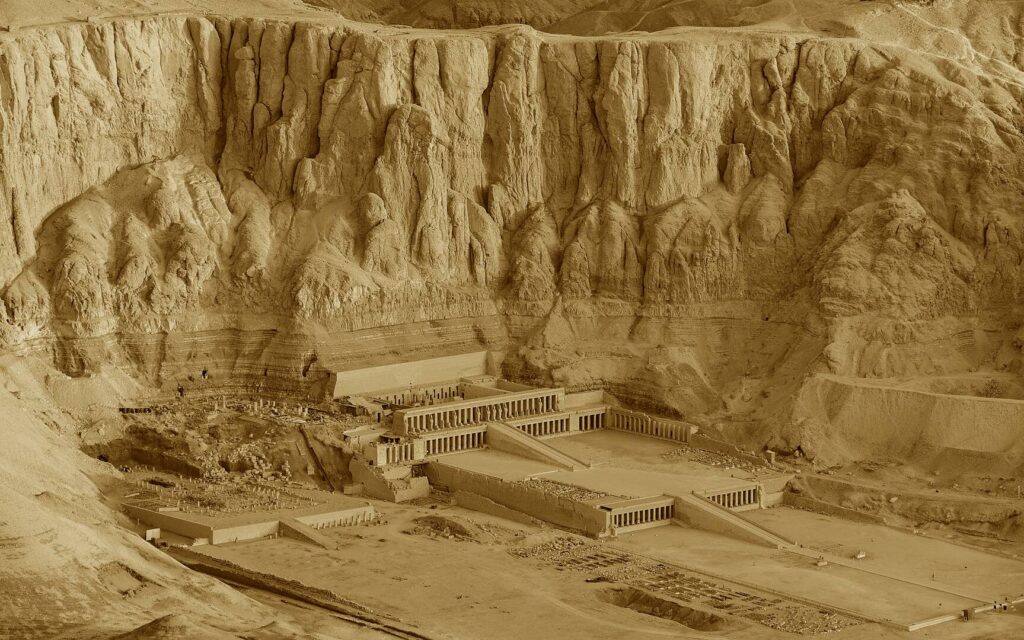

Dendara was an important administrative and religious centre as early as the 6th dynasty (c 2320 BC). Although built at the very end of the Pharaonic period, the Temple of Hathor is one of the iconic Egyptian buildings, mostly because it remains largely intact, with a great stone roof and columns, dark chambers, underground crypts and twisting stairways, all carved with hieroglyphs.

All visitors must pass through the visitors centre with its ticket office and bazaar. While it is still mostly unoccupied, before long this may involve running the gauntlet of hassling traders to get to the temple. One advantage is a clean, working toilet. At the time of our visit, it was not possible to buy food or drinks at the site.

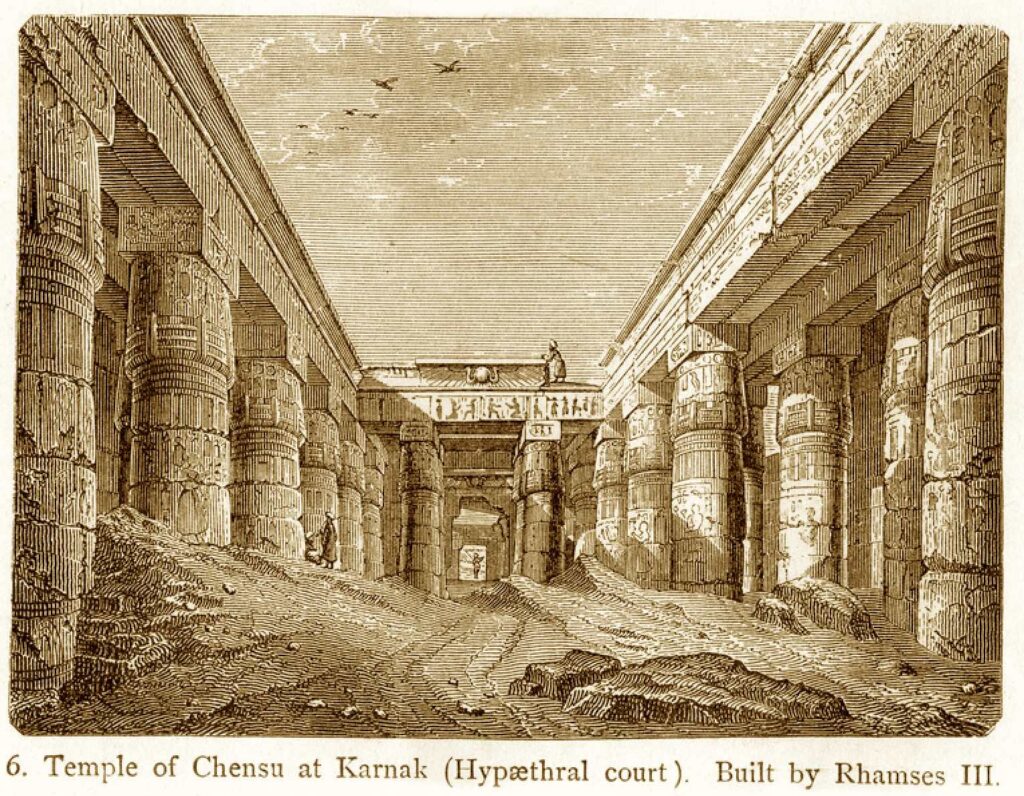

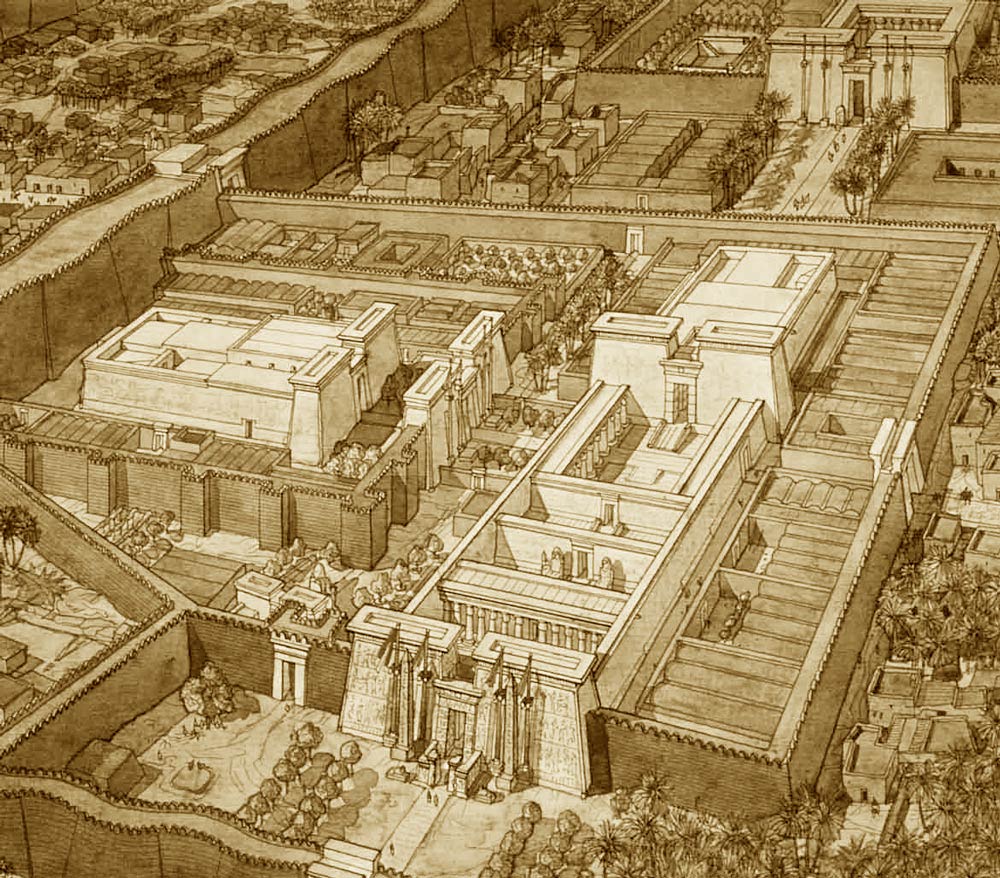

Beyond the towering gateway and mud walls, the temple was built on a slight rise. The entrance leads into the outer hypostyle hall, built by Roman emperor Tiberius, the first six of its 24 great stone columns adorned on all four sides with Hathor’s head, defaced by Christians but still an impressive sight. The walls are carved with scenes of Tiberius and his Roman successors presenting offerings to the Egyptian gods: the message here, as throughout the temple, is the continuity of tradition, even under foreign rulers. The ceiling at the far left and right side of the hall is decorated with zodiacs. One section has now been cleaned and the colours are very bright.

The inner temple was built by the Ptolemies. The smaller inner hypostyle hall again has Hathor columns and walls carved with scenes of royal ceremonials, including the founding of the temple. But notice the ‘blank’ cartouches that reveal much about the political instability of late Ptolemaic times – with such a rapid turnover of pharaohs, the stonemasons seem to have been reluctant to carve the names of those who might not be in the job for long. Things reached an all-time low in 80 BC when Ptolemy XI murdered his more popular wife and stepmother Berenice III after only 19 days of co-rule. The outraged citizens of Alexandria dragged the pharaoh from his palace and killed him in revenge.

Beyond the second hypostyle hall, you will find the Hall of Offerings leads to the sanctuary, the most holy part of the temple, home to the goddess’ statue. A further Hathor statue was stored in the crypt beneath her temple, and brought out each year for the New Year Festival, which in ancient times fell in July and coincided with the rising of the Nile. It was carried into the Hall of Offerings, where it rested with statues of other gods before being taken to the roof. The western staircase is decorated with scenes from this procession. In the open-air kiosk on the southwestern corner of the roof, the gods awaited the first reviving rays of the sun-god Ra on New Year’s Day. The statues were later taken down the eastern staircase, which is also decorated with this scene.

The theme of revival continues in two suites of rooms on the roof, decorated with scenes of the revival of Osiris by his sister-wife, Isis. In the centre of the ceiling of the northeastern suite is a plaster cast of the famous ‘Dendara Zodiac’, the original now in the Louvre in Paris. Views of the surrounding countryside from the roof are magnificent.

The exterior walls feature lion-headed gargoyles to cope with the very occasional rainfall and are decorated with scenes of pharaohs paying homage to the gods. The most famous of these is on the rear (south) wall, where Cleopatra stands with Caesarion, her son by Julius Caesar.

Facing this back wall is a small temple of Isis built by Cleopatra’s great rival Octavian (the Emperor Augustus). Walking back towards the front of the Hathor temple on the west side, the palm-filled Sacred Lake supplied the temple’s water. Beyond this, to the north, lie the mudbrick foundations of the sanatorium, where the ill came to seek a cure from the goddess.

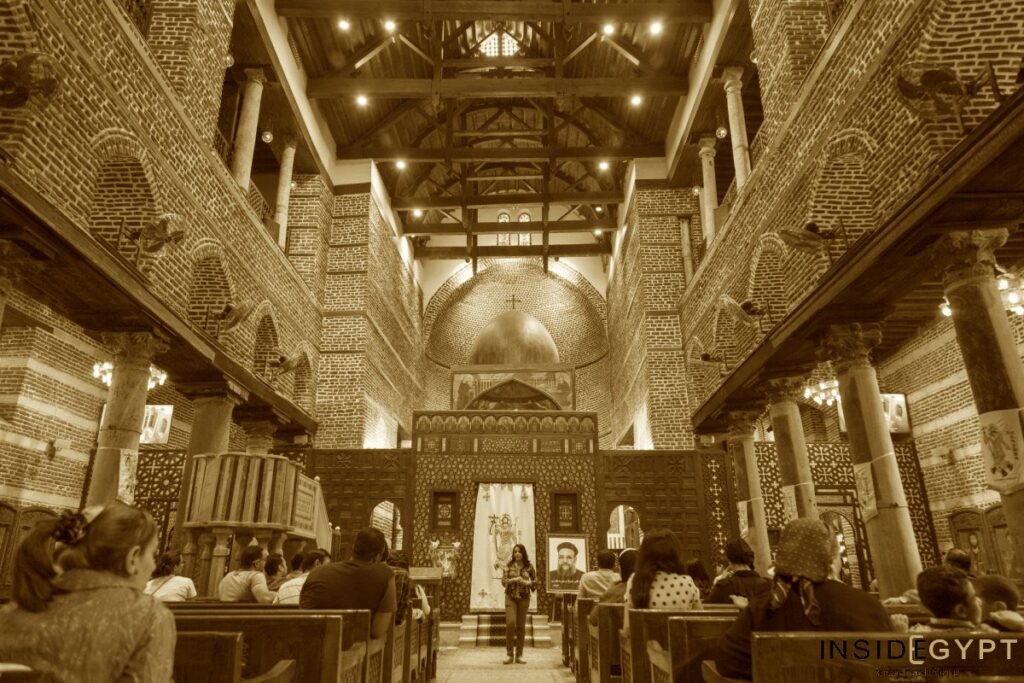

Finally there are two mammisi (birth houses): the first was built by the 30th-dynasty Egyptian pharaoh, Nectanebo I (380–362 BC), and decorated by the Ptolemies; the other was built by the Romans and decorated by Emperor Trajan (AD 98–117). Such buildings celebrated divine birth, both of the young gods and the pharaoh himself as the son of the gods. Between the mammisi lie the remains of a 5th-century-AD Coptic basilica.