Valley of the Queens

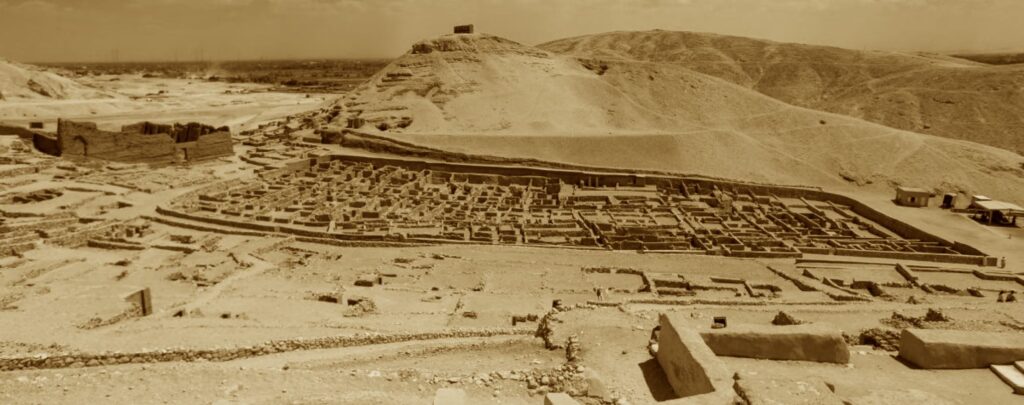

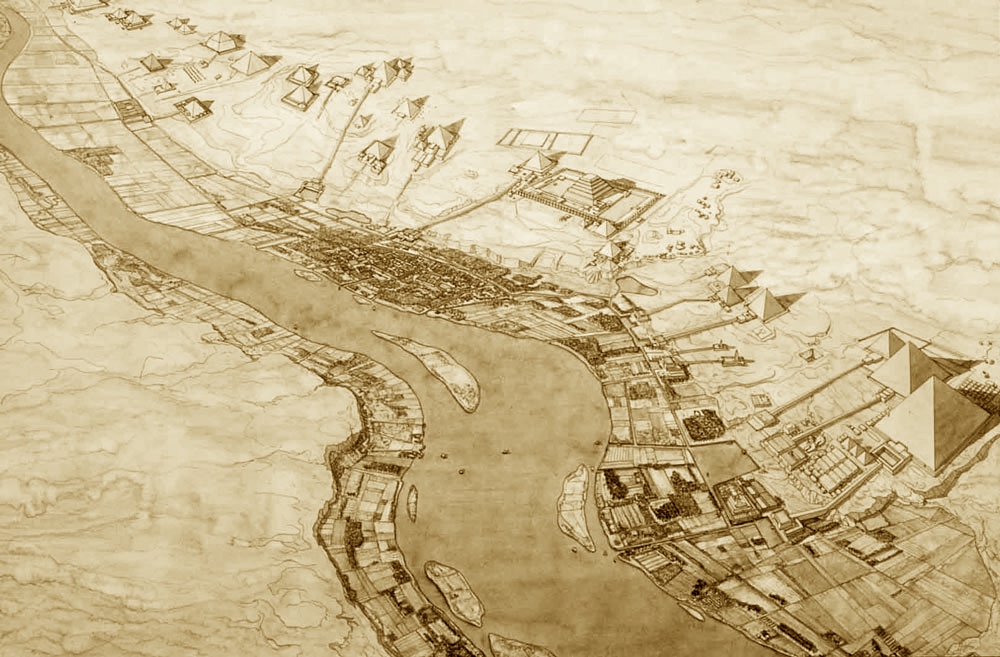

Approximately 1.5 km southwest of the Valley of the Kings, several wadis extend west from the edge of the low desert into and behind the Qurn, offering accessible but easily protected sites for burials. Here is where the tombs of many of Egypt’s New Kingdom royal family members lie. The most famous of these is the Valley of the Queens (QV). Commonly known in Arabic as Wadi Biban al-Malakat, QV has many other modern names, including Biban al Harim (“Gates of the Harim”) and Biban al Banat (“Gates of the Daughters”). Nearly all refer to female royalty, and it is their tombs for which QV is best known. However, the first people to be buried in QV were not queens but princes and princesses, sons and daughters of New Kingdom pharaohs. Indeed, the ancient name of the valley, ta set neferu, is a phrase that can mean both “The Place of Beauty” and “The Place of (Royal) Children”. The earliest burials in the QV date to the 18th

Dynasty and were nearly all of royal offspring. It is only from the early 19th Dynasty onward that royal wives and mothers were also interred here. It is worth noting that a relatively small number of New Kingdom royal wives, sons, and daughters were buried in QV and nearby wadis in comparison to what is found in the historical record.

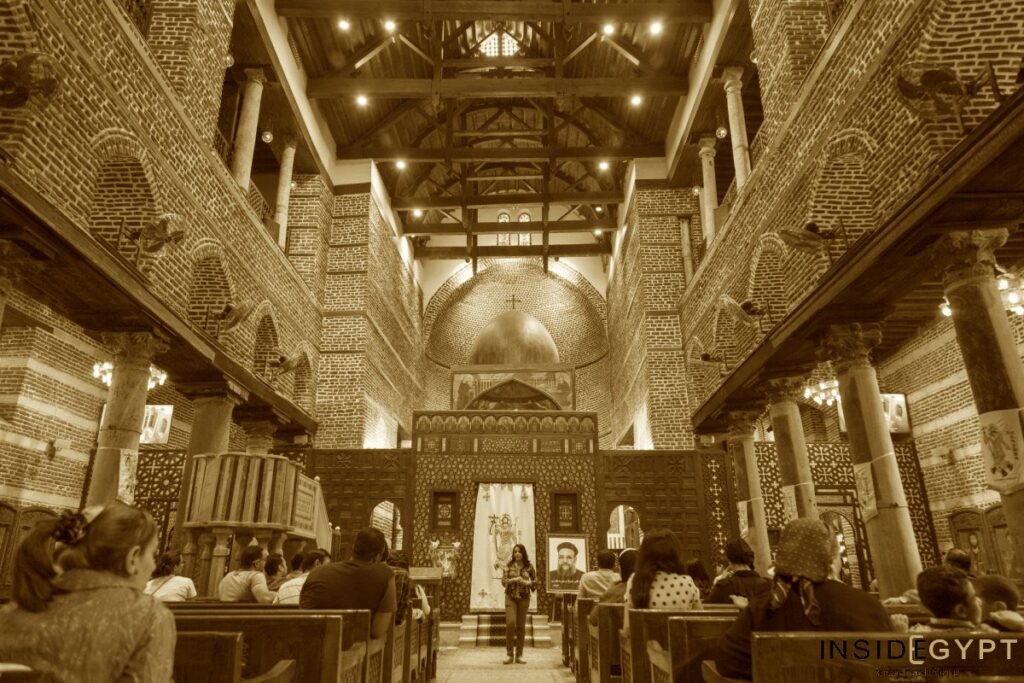

Lying close to the QV are 3 subsidiary wadis that were also used as burial sites for royal family members and elite officials. The tomb of Prince Ahmose (QV 88) was dug in the eponymous Valley of Prince Ahmose, together with that of an anonymous person (QV 98). Several Christian hermitages (called laurae) were later built here as well. The Valley of the Rope (Vallée du Cord, Wadi Habl), named by European visitors for a length of ancient rope hanging down a nearby cliff face, was the site chosen for several 18th Dynasty tombs (QV 92, QV 93, and QV 97). Lastly, the Valley of Three Pits (Vallée des Trois Puits) contains three shaft tombs (QV 89, QV 90, QV 91) and twelve smaller tombs of the Thutmosid Period (QV A through QV L).

The numbering system now used in the QV and subsidiary wadis was developed by Ernesto Schiaparelli and Francesco Ballerini of the Turin Museum Italian Archaeological Expedition that excavated in the area from 1903-1905. The original plaques erected by Schiaparelli and Ballerini to commemorate a tomb’s discovery can still be found at a number of the entrances, including QV 44, QV 52, and QV 55. One hundred and eleven tombs have been found in QV and subsidiary wadis thus far, but the names of only about 35% of their owners are known. The others are anonymous, some because their names were never written on the tombs’ walls, some because their names and inscribed grave goods were destroyed by floods or vandalism, and some because their tomb was reused and earlier texts erased. Furthermore, only 22% of the tombs in the QV and subsidiary wadis were decorated. The 18th Dynasty tombs were either left bare or plastered over and it is only from the 19th Dynasty onwards that the walls were decorated with images of the deceased offering to or adoring deities and scenes from various funerary books.

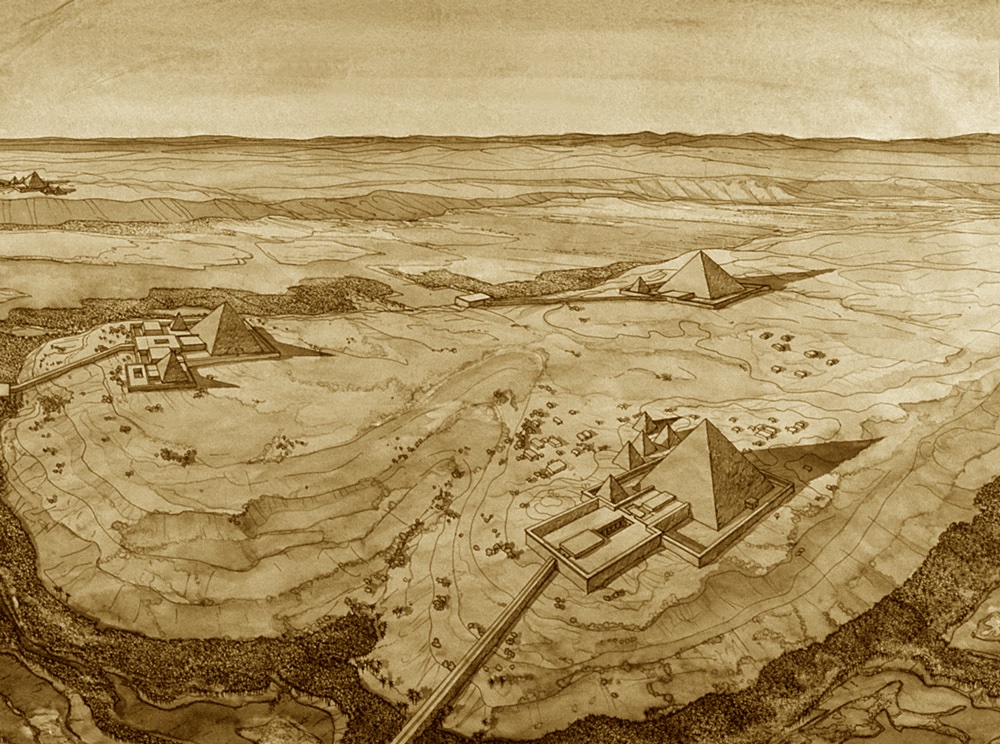

About two kilometers west of the QV, several large wadi systems cut deep into steep cliffs that define the back of the Qurn. These are collectively known as the Western Wadis. The area’s magnificent scenery has been remarked upon by nearly every archaeologist who has made the trek.

Elizabeth Thomas wrote that “beauty alone … would make its exploration a pleasure.” Howard Carter observed that there was “no doubt” these wadis were cemeteries for 18th Dynasty royal wives and daughters, and that beauty and isolation were features that probably led ancient Egyptians to choose them, together with the more easily accessible Valley of the Queens. The Western Wadis refers to three wadi complexes in the area. Wadi Jabbanat el-Qurud includes several smaller wadis designated by Howard Carter as A, B, C, and D. Its name means ‘Cemetery of the Apes’, due to the fact that 19th century explorers found Late or Ptolemaic burials of over a hundred mummified baboons in Wadi D. Wadi A is the location of two cliff tombs, Wadi A-1 and Wadi A-2, as well as two pit tombs, Wadi A-3 and Wadi A-4. While Wadi A-2 is anonymous, Wadi A-1 was cut for Hatshepsut before her accession to the throne. Neferure, a daughter of Hatshepsut, may have been buried in a cliff tomb in Wadi C (Wadi C-1), although some have suggested it is the tomb of Merytra, principal wife of Thutmes III. A tomb in Wadi D (Wadi D-1), variously and confusingly also labelled HC 70, ET B, and D1 by various archaeologists, was dug for three Syrian princesses and minor queens of Thutmes III. Wadi al Gharbi, which includes Wadis E, F, and G, is the largest and most distant of the outliers. Some believe that the 20th Dynasty tomb of the High Priest and last pharaoh at Thebes, Herihor, may lie here undiscovered in Wadi F. However, this is unproved and considered doubtful by many. Lastly, a large complex of subterranean shaft tombs, WB 1, lie further west in Wadi al-Bariyah. In contrast to the hidden cliff tombs of Wadis A-D, these shaft tombs were excavated into a mound some 15m above the broad, flat flood-plain. The burial equipment discovered in and associated with these tombs indicate that they belonged to members of the royal court of Amenhetep III. Most recently, the joint mission between the New Kingdom Research Foundation and the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities discovered a new royal tomb in Wadi C. This tomb most likely belonged to a great royal wife and several children of a Thutmoside king. The Western Wadis thus served as a precursor to the Valley of the Queens as the burial place of senior members of the royal family, namely Queens. The reason for the shift from the outlying wadis to the QV in the 19th Dynasty is unknown, but may be due to the easier accessibility of the latter.

Along a path leading from the QV to Dayr al-Madinah, a sanctuary was cut into the bedrock in the late 18th Dynasty in an area now known as the Valley of the Dolmen. It consists of seven chapels for Ptah and Meretseger, deities closely associated with the Theban necropolis and QV. Two man-made structures further along the path, termed “dolmen” and a “menhir” by early European travelers, were also sites of New Kingdom activity. The menhir was a small stone structure with several rooms that may have served as a place of shelter or worship for workmen. The dolmen was a small chamber built of stacked blocks that perhaps served similar functions. In the New Kingdom, security in QV and the surrounding area was maintained by small, stone guard huts along the ridge west of QV and nearby burial sites.