Horemheb

Horemheb (reigned 1320-1292 BCE) was the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty of Egypt. He is also known as Dejserkheprure and Horemhab. His name means, “Horus is in Festival” and he came from the lower classes of Egypt, worked himself up through the ranks of the army, became commander-in-chief of the Egyptian military, and finally pharaoh.

Horemheb as scribe, Museum of Metropolitan Art, New York

Little is known about his early life, but it seems that he initially served under Amenhotep III and continued service under Akhenaten. He first comes to the notice of historians during the reign of Tutankhamun when he acted in the capacity of advisor to the young king along with the vizier Ay.

Ay succeeded Tutankhamun and, on his death, Horemheb took the throne, at which point he initiated a nation-wide campaign to erase his immediate predecessor’s names from history and revitalize the nation that had declined under Akhenaten’s rule. He is generally considered a good pharaoh, but whether he is a hero or villain depends upon one’s view of Akhenaten’s reign and Horemheb’s reaction to it.

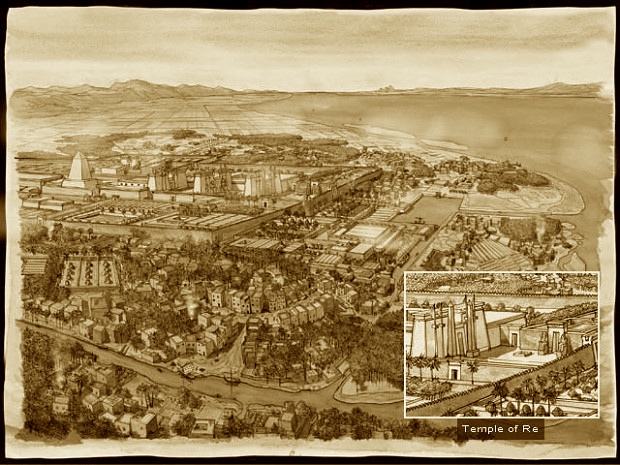

Based upon his coronation text, Horemheb came from the city of Herakleopolis, but nothing is known of his parentage nor anything of his youth. He first appears in the historical record serving under Amenhotep III but, as this reference is unclear, he could have begun his career under Akhenaten. It would seem, however, that since he was quickly promoted by Akhenaten to Great Commander of the Army, he would have provided service to the throne earlier.

Akhenaten initiated religious reforms that proscribed the traditional polytheistic religious practices in Egypt and instituted monotheism in the form of the religion of Aten. Aten had been a minor sun deity prior to Akhenaten’s reign but now became the supreme god of the universe and the only god the Egyptians were allowed to worship.

Further, Akhenaten proclaimed himself the incarnation of Aten and elevated his wife, Nefertiti, to equally divine status. Thus, the royal couple were not only the intermediaries between the people of Egypt and their god, they were the god incarnate. Whatever Horemheb may have thought of these reforms at the time is unknown but, based upon his later reaction to them, he did not approve. There would have been good reason for his displeasure. The historian Barbara Watterson notes that:

By the ninth year of his reign, Akhenaten had proscribed the old gods of Egypt, and ordered their temples to be closed, a very serious matter, for these institutions played an important part in the economic and social life of the country. Religious persecution was new to the Egyptians, who had always worshipped many deities and were ever ready to add new gods to the pantheon. Atenism, however, was a very exclusive religion confined to the royal family, with the king as the only mediator between man and god. (111-112)

Still, Horemheb served his king as commander-in-chief and led the armies of Egypt against the Hittites in the north. If he did serve under Amenhotep III, then his frustration under Akhenaten must have been immense in that the inscriptions relate that the Egyptian army, once invincible, was unable to win a single victory against the Hittites during Akhenaten’s reign.

The cause of this is thought to be the king’s neglect of both foreign and domestic affairs due to his intense religious interests. Nefertiti assumed the responsibilities of her husband but, in spite of her efforts, Egypt continued to decline in power. The military exercises and discipline, which had been a regular part of the army’s life under Amenhotep III, had grown lax as, in fact, had every other aspect of Egyptian rule save that of Akhenaten’s monotheistic faith.