Seshat

Seshat (also given as Sefkhet-Abwy and Seshet) is the Egyptian goddess of the written word. Her name literally means “female scribe” and she is regularly depicted as a woman wearing a leopard skin draped over her robe with a headdress of a seven-pointed star arched by a crescent in the form of a bow.

This iconography has been interpreted as symbolizing supreme authority in that it is common in Egyptian legend and mythology for one to wear the skin of a defeated enemy to take on the foe’s powers, stars were closely associated with the realm of the gods and their actions, and the number seven symbolized perfection and completeness.

The leopard skin would represent her power over, and protection from, danger as leopards were a common predator. The crescent above her headdress, resembling a bow, could represent dexterity and precision, if one interprets it along the lines of archery, or simply divinity if one takes the symbol as representing light, along the lines of later depictions of saints with halos.

This iconography has been interpreted as symbolizing supreme authority in that it is common in Egyptian legend and mythology for one to wear the skin of a defeated enemy to take on the foe’s powers, stars were closely associated with the realm of the gods and their actions, and the number seven symbolized perfection and completeness.

The leopard skin would represent her power over, and protection from, danger as leopards were a common predator. The crescent above her headdress, resembling a bow, could represent dexterity and precision, if one interprets it along the lines of archery, or simply divinity if one takes the symbol as representing light, along the lines of later depictions of saints with halos.

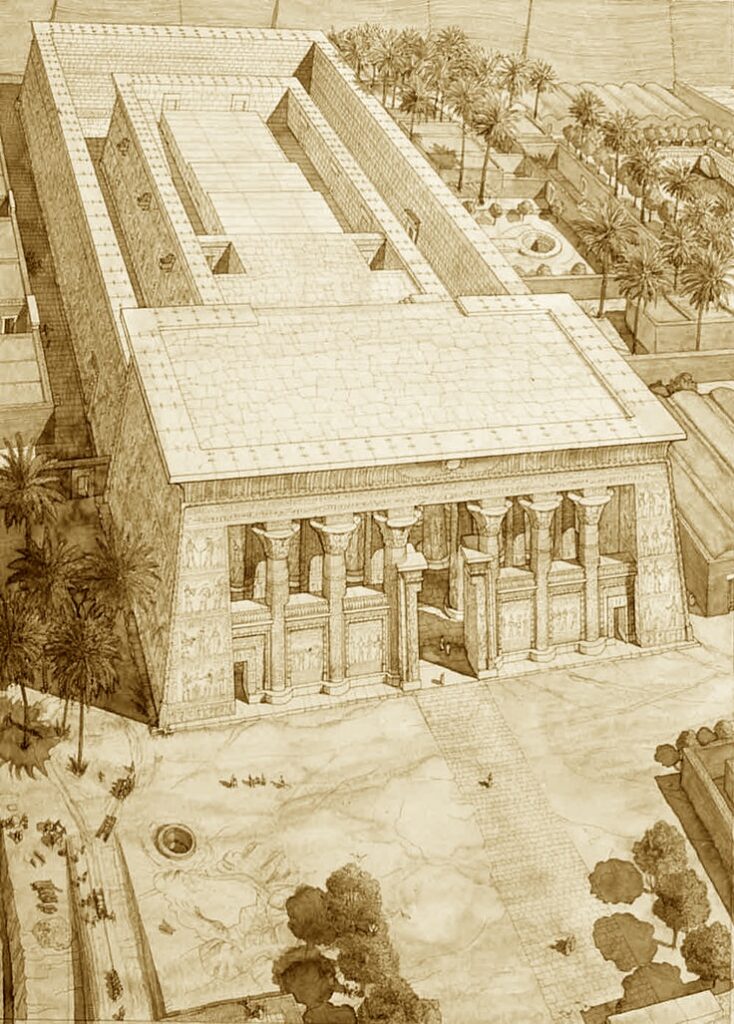

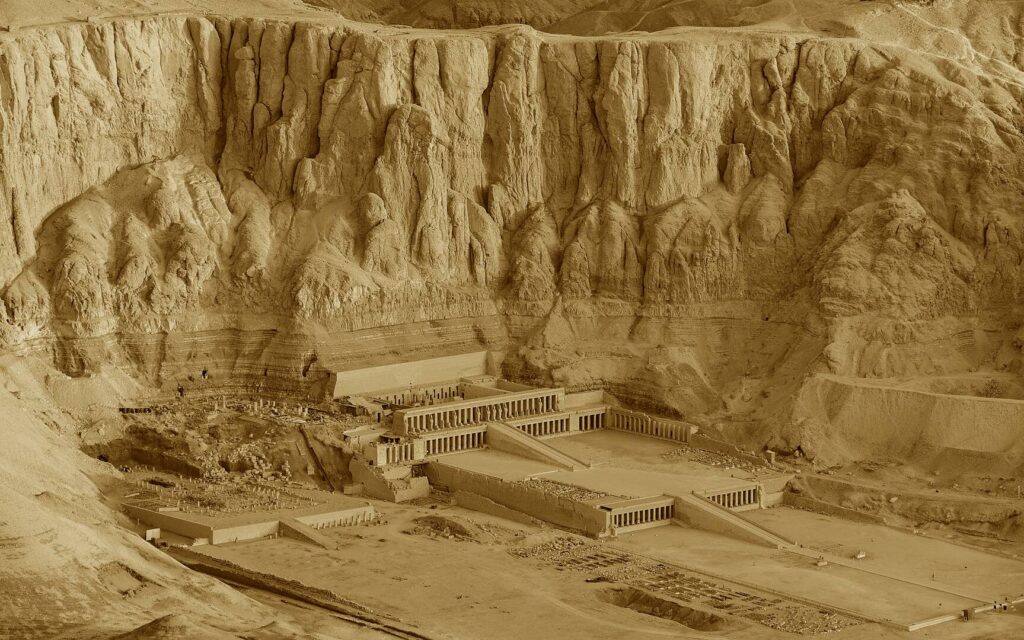

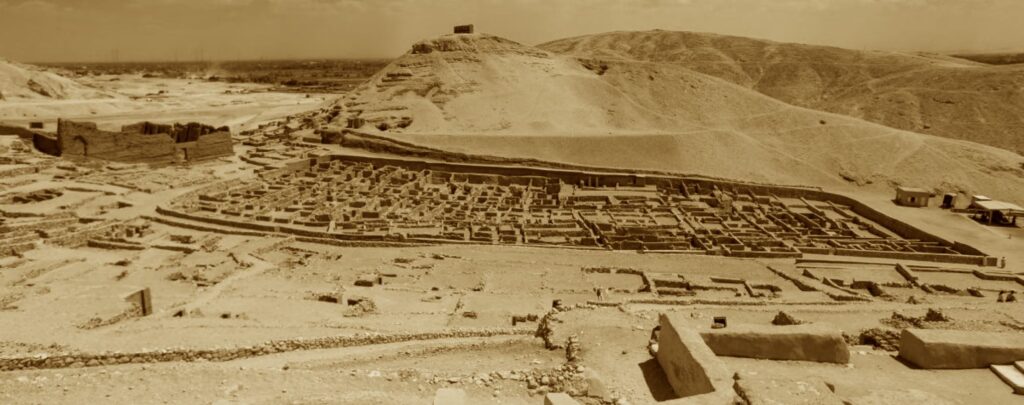

Among her responsibilities were record keeping, accounting, measurements, census-taking, patroness of libraries and librarians, keeper of the House of Life (temple library, scriptorium, writer’s workshop), Celestial Librarian, Mistress of builders (patroness of construction), and friend of the dead in the afterlife. She is often depicted as the consort (either wife or daughter) of Thoth, god of wisdom, writing, and various branches of knowledge.

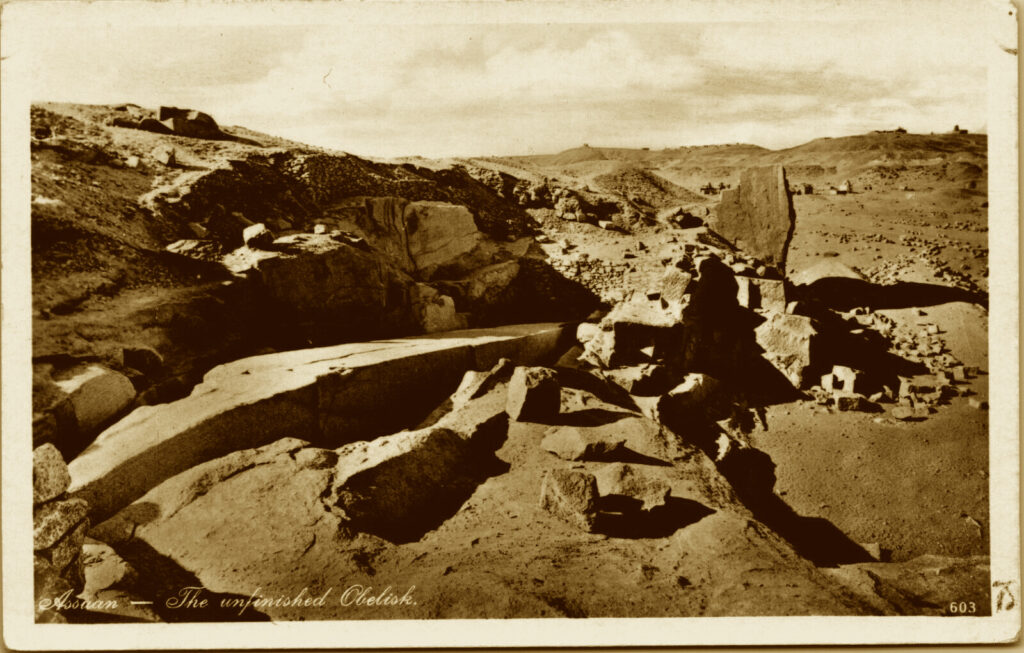

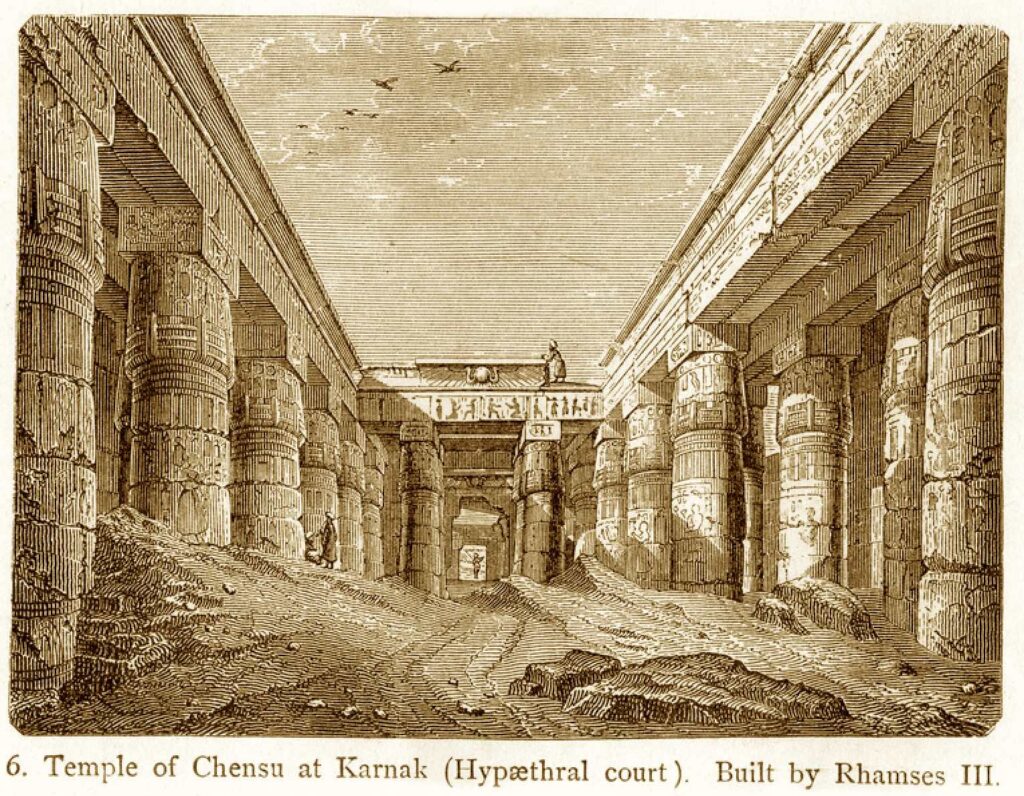

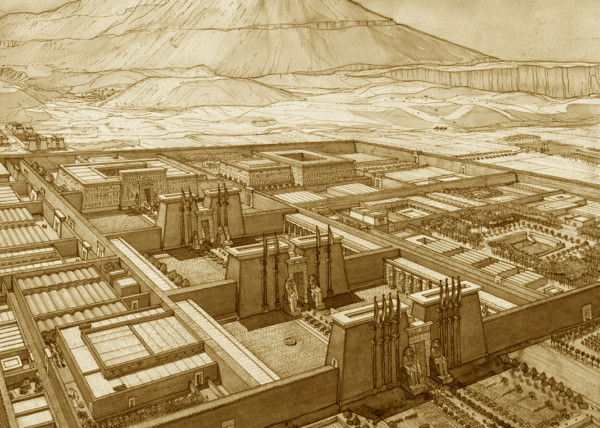

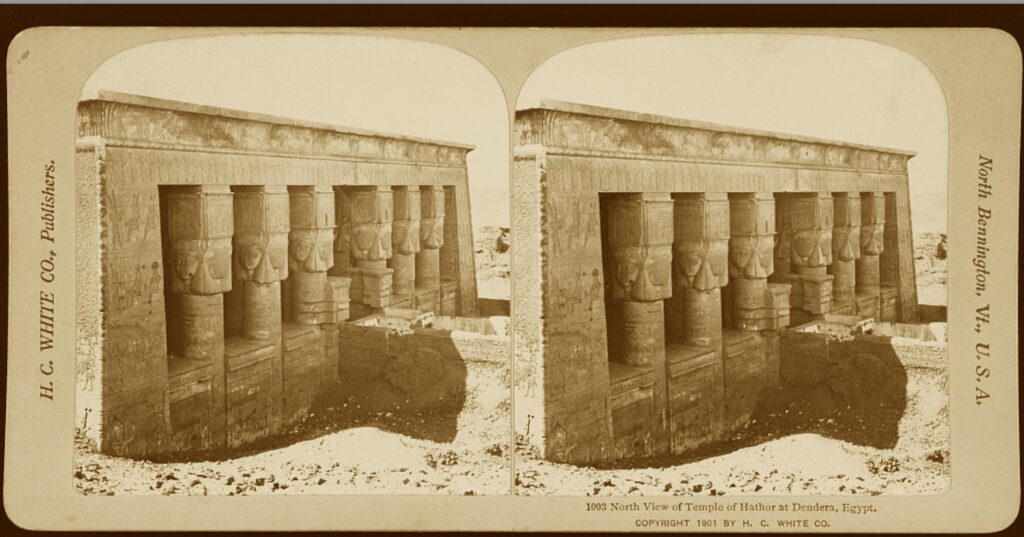

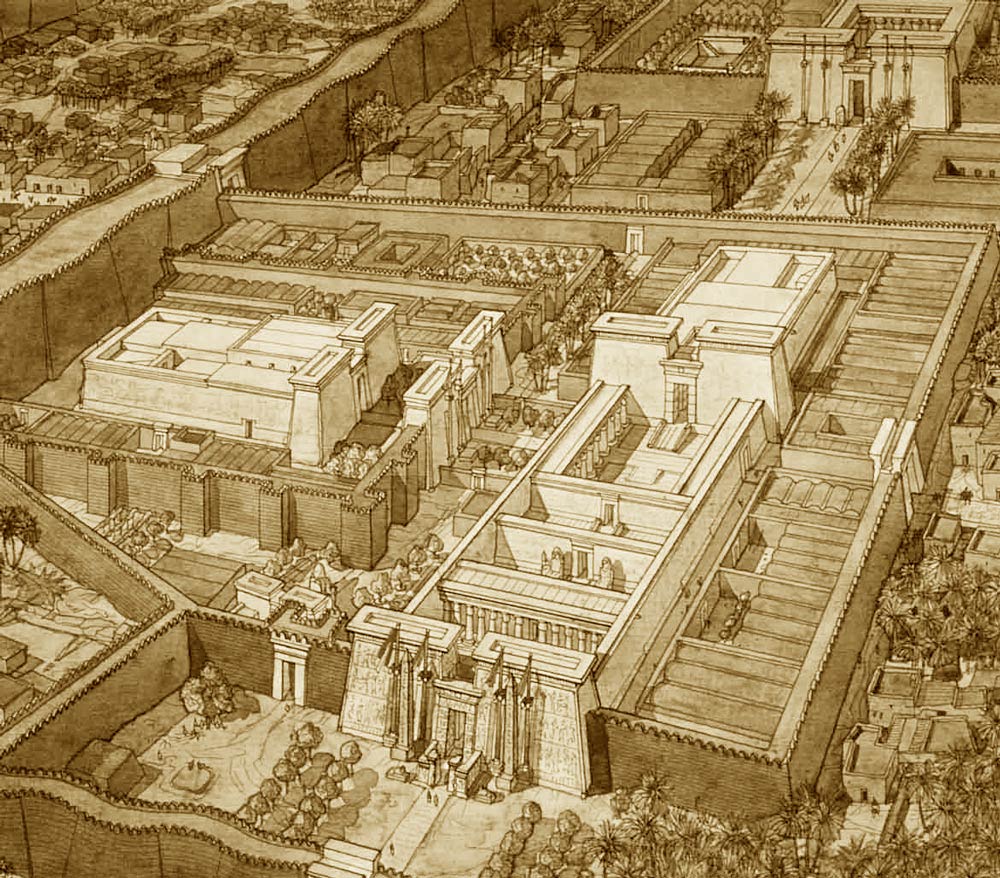

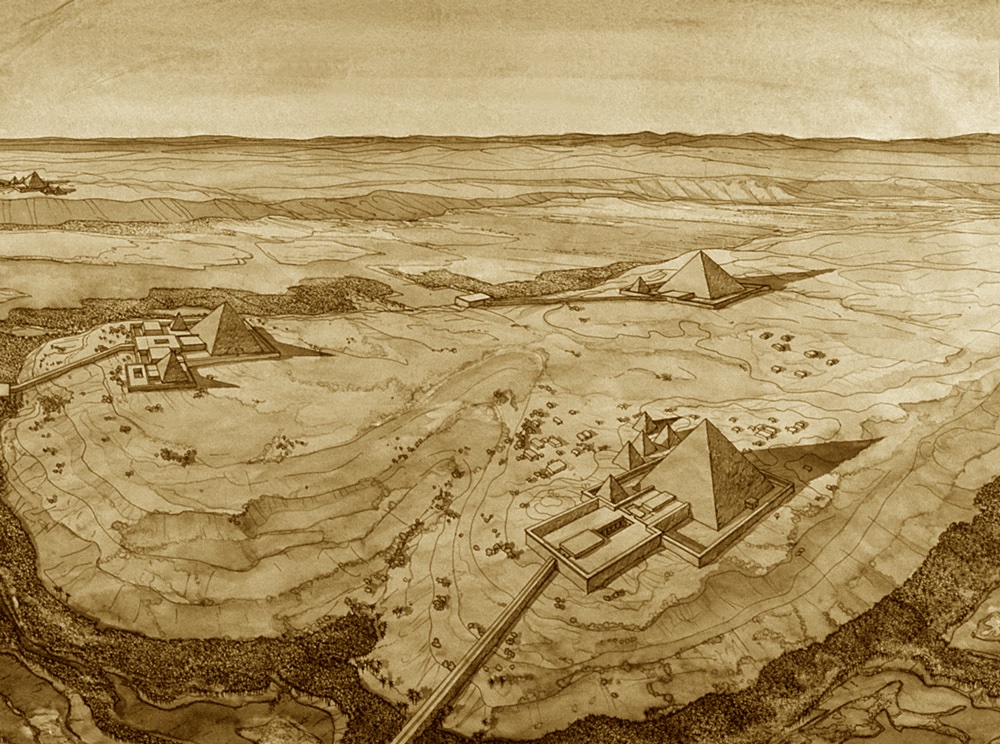

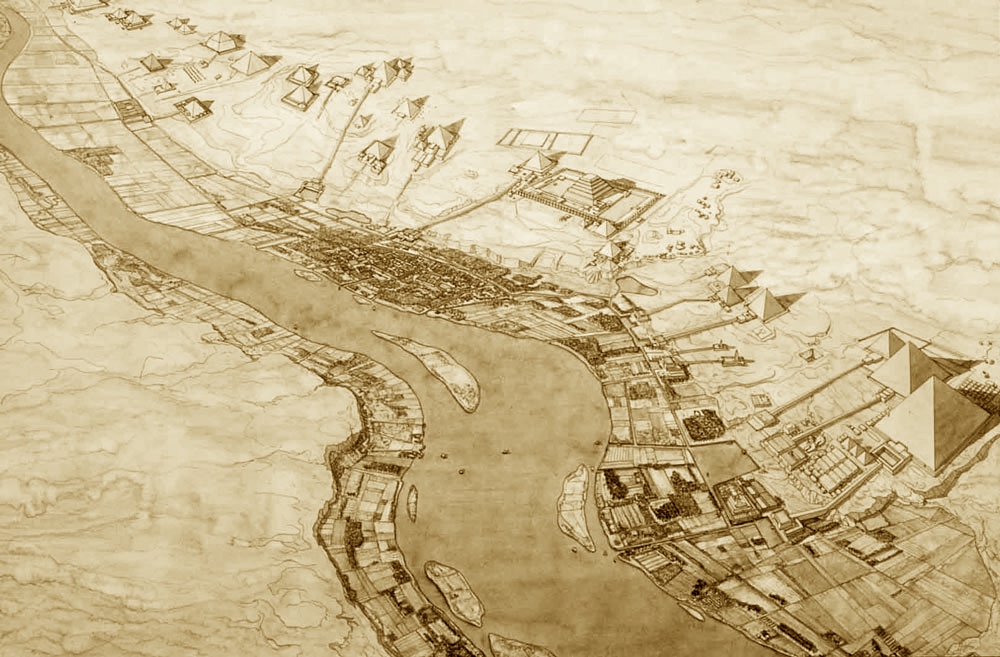

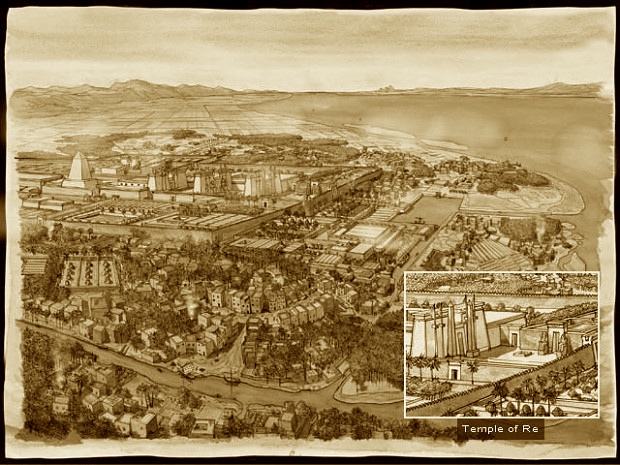

She first appears in the 2nd Dynasty (c. 2890- c. 2670 BCE) of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE) as a goddess of writing and measurements assisting the king in the ritual known as “stretching of the cord” which preceeded the construction of a building, most often a temple.

The ancient Egyptians believed that what was done on earth was mirrored in the celestial realm of the gods. The daily life of an individual was only part of an eternal journey which would continue on past death. Seshat featured prominently in the concept of the eternal life granted to scribes through their works. When an author created a story, inscription, or book on earth, an ethereal copy was transferred to Seshat who placed it in the library of the gods; mortal writings were therefore also immortal.

She first appears in the 2nd Dynasty (c. 2890- c. 2670 BCE) of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE) as a goddess of writing and measurements assisting the king in the ritual known as “stretching of the cord” which preceeded the construction of a building, most often a temple.

The ancient Egyptians believed that what was done on earth was mirrored in the celestial realm of the gods. The daily life of an individual was only part of an eternal journey which would continue on past death. Seshat featured prominently in the concept of the eternal life granted to scribes through their works. When an author created a story, inscription, or book on earth, an ethereal copy was transferred to Seshat who placed it in the library of the gods; mortal writings were therefore also immortal.

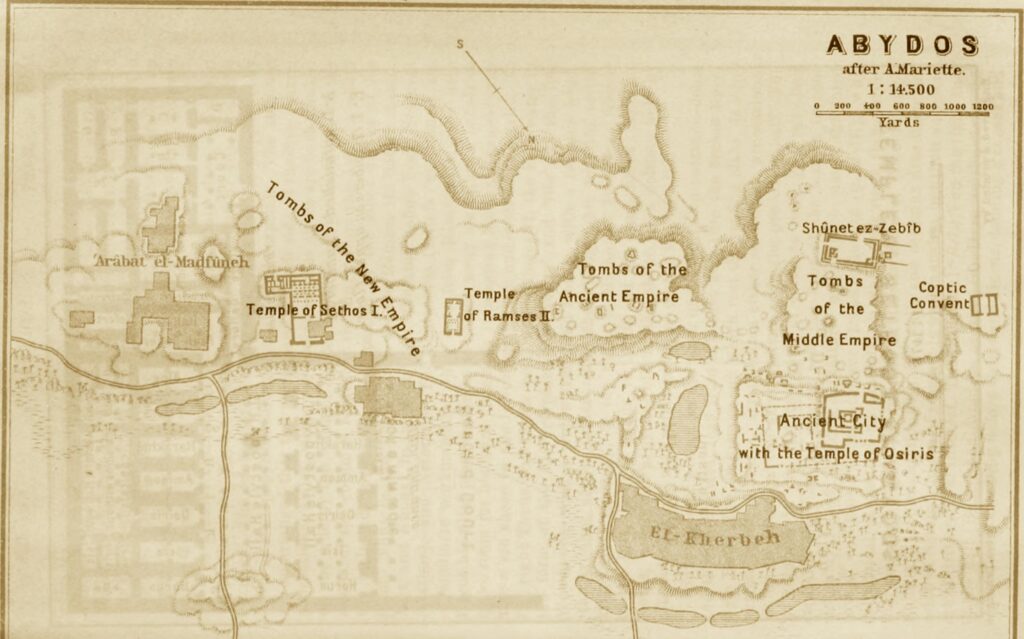

Seshat was also sometimes depicted helping Nephthys revive the deceased in the afterlife in prepration for their judgment by Osiris in the Hall of Truth. In this capacity, the goddess would have helped the new arrival recognize the spells of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, enabling the soul to move on toward the hope of paradise.

Unlike the major gods of Egypt, Seshat never had her own temples, cult, or formal worship. Owing to the great value Egyptians placed on writing, however, and her part in the construction of temples and the afterlife, she was venerated widely through commonplace acts and daily rituals from the Early Dynastic Period to the last dynasty to rule Egypt, the Ptolemaic Dynasty of 323-30 BCE. Seshat is not as well known today as many of the other deities of ancient Egypt but, in her time, she was among the most important and widely recognized of the Egyptian pantheon.

Unlike the major gods of Egypt, Seshat never had her own temples, cult, or formal worship. Owing to the great value Egyptians placed on writing, however, and her part in the construction of temples and the afterlife, she was venerated widely through commonplace acts and daily rituals from the Early Dynastic Period to the last dynasty to rule Egypt, the Ptolemaic Dynasty of 323-30 BCE. Seshat is not as well known today as many of the other deities of ancient Egypt but, in her time, she was among the most important and widely recognized of the Egyptian pantheon.